LES AMOUREUX DU CINÉMA

L'ÉVÉNEMENT (2021) - ANNIE ERNAUX

The Federation of Alliances Françaises USA

An adaptation of Annie Ernaux's eponymous novel, the French film "Happening," focuses on Anne, a bright college student who wants to finish her studies to escape her working-class background. One day, her life is changed by an unexpected pregnancy. Living in 1960s France where abortion was still illegal, Anne must take matters into her own hands.

L'événement / Happening (2021)

Director: Audrey Diwan

Starring: Anamaria Vartolomei, Kacey Mottet Klein, Luàna Bajrami, Louise Orry-Diquéro

You are encouraged to watch the film via streaming before attending the discussion.

Recorded Discussion Available on Youtube - CLICK HERE

Become a Member of Alliance SRQ and enjoy more cultural programs & events!

CLICK HERE NOW TO JOIN!

***************************************************************************************************************************

QUAND LE CINÉMA FAIT DE LA POLITIQUE

Three Wednesdays - 12, & 26 March & 02 April 2025 from 4:00 pm - 5:30pm

Join us beginning Wednesday 12 March 2025 as we discuss IN FRENCH on ZOOM our three French films (no session on 19 March). Each Wednesday session runs 1½-hours.

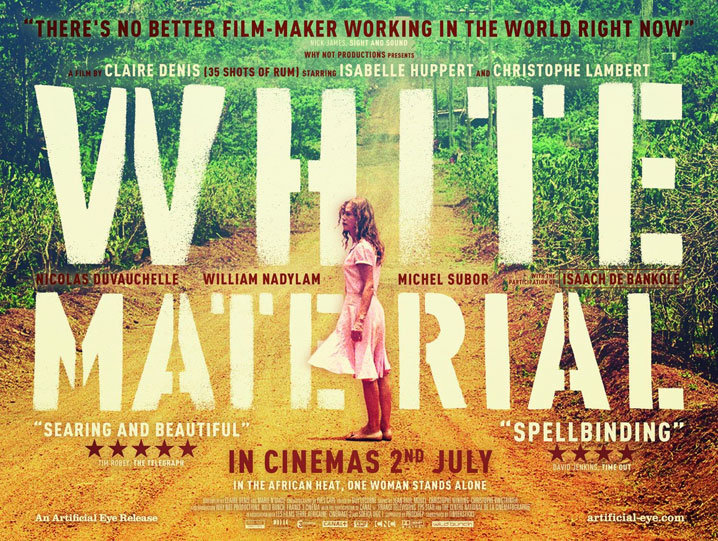

- White Material , Claire DENIS (2009)

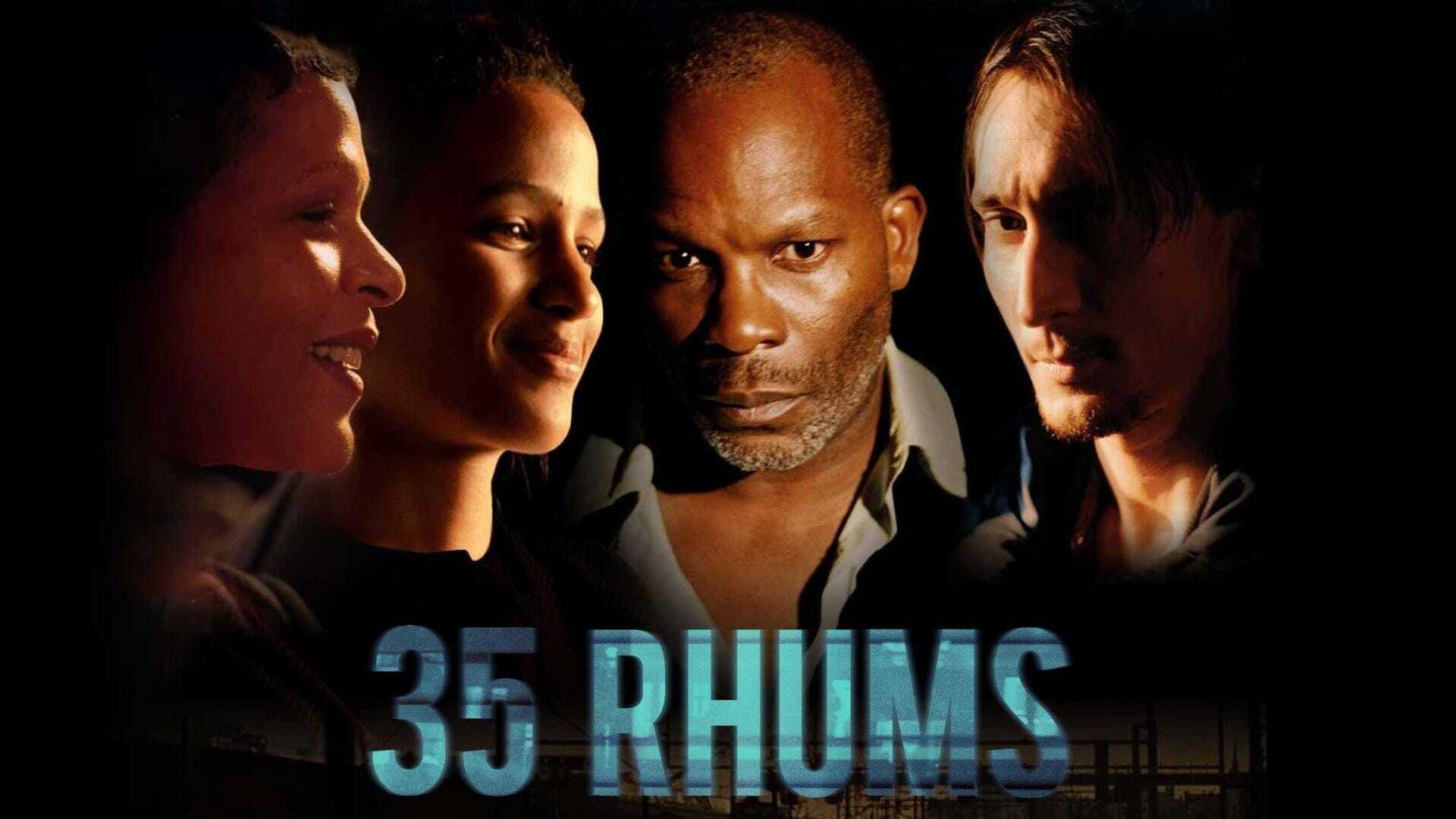

- 35 Rhums (35 Shots of Rum), Claire DENIS (2008)

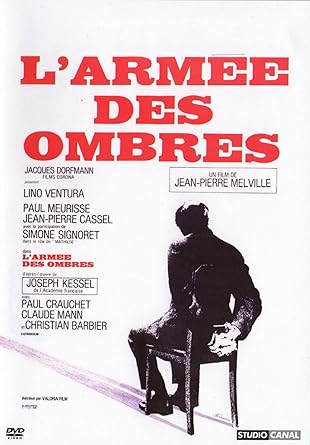

- L'Armée des Ombres (Army of Shadows), J.P. MELVILLE (1969)

For decades, France has been and remains a country where directors immigrate from all over the world to make political films freely, and French productions have continuously challenged forms of power and censorship

Analyzing French political films provides a unique lens through which to view the intersecting realms of art, politics, and history. These films serve as vibrant narratives that address and reflect upon the pressing socio-political issues of their times. Through the medium of cinema, filmmakers offer critiques, highlight injustices, and explore the complexities of the human condition within specific political contexts.

The films in our series share a connection to France, the French-speaking world, and the French cinematic tradition.

You will be expected to see the four films on your own before each discussion. All four films are available with English subtitles for a nominal rental fee on Amazon Prime (links provided upon registration). One week in advance of each showing, we will provide vocabulary lists, and suggest possible discussion topics prior to the session, all designed to inspire a lively debate.

We look forward to seeing you at our 43-week ZOOM session, beginning Wednesday 12 March at 4:00 pm (no class Wednesday 19 March) as we explore the unique perspectives of our selected French filmmakers.

To sign-up, go to the French classes page and FRENCH FILM SERIES "QUAND LE CINÉMA FAIT DE LA POLITIQUE" WITH TESS

Three 1½-hour discussions IN FRENCH on ZOOM - $150